The Waldensian Movement From Waldo to the Reformation

Author

Dennis McCallum

Introduction

In the literature of the eleventh and twelfth centuries, there appears the figure of an intriguing man who had an exceptional impact on the society of his day. He is referred to variously as Valdes, Valdesius, Valdensius and Waldo (Valdo), from the city of Lyons.

References to the movement he founded ("Waldensians" "the poor of Lyons" "the Leonese" "the Poor of Lombardy" or simply "the Poor") appear repeatedly throughout the succeeding centuries of European history. They are always in the shadows, always under bitter persecution, always hard to understand, but always seemingly at the cutting edge of reformation ferment.

Historiography

The actions and views of Waldo are shrouded in shadow, because neither he, nor contemporaries in his movement ever chronicled their lives. No existing documents speak of the exact year of his birth, of his youth, or even of the very last years of his life.1 This problem is made worse by the fact that the Poor of Lyons themselves desired to establish an argument for their legitimacy based on antiquity.

In a day when there was only one legitimate church, the Poor of Lyons felt that they had to answer the charge that they must be heretics because they were new. Therefore, they developed an argument that they were the remnant of a movement that had been resisting the Roman Catholic Church since the time of Constantine's donation of the western empire to Pope Sylvester in the fourth Century AD. This claim depended on the spurious documentation for the donation of Constantine, which both Catholics and Waldensians believed to be authentic at the time but which is actually without historical support.2

This development would have been harmless enough, but unfortunately, some early Protestant historians, writing in the 1600's were also in the market for a claim to antiquity. They saw the Waldensians as the bridge between themselves and the Apostles.3 They were inclined to believe the legends of the Poor of Lyons, and unfortunately they had possession of the earliest authentic Waldensian manuscripts.

These documents were compiled with commentary in a history written by Perrin, pastor at Lyons in the year 1618.4 Perrin's history was commissioned by the Synod of Dauphiny (which included the now reformed Waldensian Churches).5 A few years later, in 1655, John Leger, a Waldensian pastor, compiled another collection of source material, which eventually wound up in the library of the University of Cambridge.6 Perrin and Leger attributed dates to the documents which were far too early. Some Waldensians documents were dated as early as 1100 AD, (at least 60 years before the movement began). Other documents from the reformation period were dated as coming from before the reformation. This had the effect of portraying the Waldensian movement as reformed in doctrine throughout their history, whereas in fact they were not reformed until after the reformation.7

In 1875, Alexis Muston published The Israel of the Alps, which, although critical of some of the earlier work, such as Perrin's,8 continued to accept the basic thesis that the Waldensians originated at the time of Sylvester. Almost every Protestant work done since the time of Muston in turn has depended on his work until recent times. In fact, studies carried out by denominations such as the Presbyterians as recently as 1912 have continued to follow this line.9 Catholic sources are no better. Melia is an example of a Roman Catholic author as recently as 1870 attempting to deny that religious persecution of the Waldensians occurred at all.10 In the same way that John Leger accepted exaggerated accounts of the persecution, Melia has accepted non-credible Roman Catholic accounts.

It is perhaps not surprising that study of the Waldensians has become unpopular among scholars because it is viewed as the province of biased ideologues. For these reasons, there are few contemporary histories of the Waldensian Movement that have scholarly credibility.11

Because of these developments, it is difficult for the average student of history to arrive at a clear picture of the chronology and development of the movement without careful comparison of contradictory material. Further, in this case one must not only compare different authors, but must also ascertain that they do not depend on each other.

All we have from the earliest period is a few fragmentary writings from letters, commentaries and poems which circulated within the group, and a larger body of contemporary material written by Roman Catholic clerics, all from a hostile point of view. Therefore, as with so many "heresies" of the medieval period, it is necessary for the student to read between the lines of detractors' comments to separate the facts of the situation from the polemical elements in the inquisitorial literature.

Beginnings

According to one report from an inquisition prosecution found in Church archives in Carcassonne, France, the movement known as the "Poor of Lyons" began in about 1170. The document goes on to state that Waldo himself had been a rich merchant who underwent a religious experience which led him to renounce all of his wealth, and ". . .observe a life of poverty and evangelical perfection, as the Apostles."12 This sort of commitment can hardly be considered unusual during this period of history. However, Waldo went further:

He arranged for the Gospels and some other books of the Bible to be translated in common speech . . . which he read very often, though without understanding their import. Infatuated with himself, he usurped the prerogatives of the Apostles by presuming to preach the Gospel in the streets, where he made many disciples, and involving them, both men and women, in a like presumption by sending them out, in turn, to preach.

These people, ignorant and illiterate, went about through the towns, entering houses and even churches, spreading many errors round about.13

Here the heart of what the Poor were all about as well as the crux of their dispute with the Roman Church is evident. Gui goes on later,

The principal heresy, then, of the aforesaid Waldensians was and still remains the contempt for ecclesiastical power. Excommunicated for this reason and delivered to Satan, they were precipitated into innumerable errors. . . The erring followers and sacrilegious masters of this sect hold and teach that they are not subject to the lord pope or Roman pontiff or to any prelates of the Roman Church. . ."14

The fact that Waldo and his followers rejected riches and lived an austere life was not objectionable to the hierarchy of the Roman Church. The same thing was being done by tens of thousands all over Europe. Neither do there seem to have been substantive doctrinal differences at first.

This last point is important, because the most intriguing aspect of the Poor is precisely that there was initially no important doctrinal difference. They saw themselves as Roman Catholics who were carrying the doctrines of Christianity further than their weaker brethren. They even sent a delegation to the third Lateran Council in 1179 to obtain Papal approval of their work. There they were examined by an English friar, Walter Mapes, who in 1184 was in Rome for the council. He recounts,

We saw Waldensian men in the Roman Council held by Pope Alexander the Third. They were simple and unlearned, and were thus called from the name of their founder, Valdo, who was a citizen of Lyons on the Rhone. They presented to the Pope a book written in the old Provencal language,15 in which there were texts and comments of the Psalms, and of many books of the Old and New Testament.16

Mapes questioned them at the council along the following lines,

Do you believe in God the Father? They answered, "We believe." And in God the Son? They answered "We believe" And in God the Holy Spirit? They answered, "We believe." And in the mother of Christ? They answered "We believe". . .

At this point the court broke out in laughter because according to Scholastic Theology, one could only use the formula "believe in" with reference to the Trinity. After this conversation, the delegation "withdrew, covered with disgrace," because they had fallen for a trick question.17 They were ordered to cease preaching, and obey their bishop.

It is easy to see from this incident that there was no serious issue of doctrine at stake. The Waldensian dispute then, centered on the issue of authority. It was the fact that they translated the scriptures, studied them, and "presumed" to preach what they believed, without reference to the clergy that was unacceptable.18 Melia declares,

. . .when John a Bellismanibus, Archbishop of Lyons, about the year 1182 . . .forbade them both to preach and . . .expelled them from his diocese; no mention was made of their holding any doctrine at variance with the teaching of the Church: they were simply expelled because, being laymen and illiterate, . . . they presumed, against the prohibition of their superiors, to preach, and exercise an office which was confided to the Apostles and to their successors only.19

They were arguing that they could draw insight directly from the pages of their translated Bibles rather than from the Roman Church.20 As one of our earliest sources, Alan of Lille put in his chapter entitled, "By what authority and for what reason it is shown that no one ought to preach unless he has permission from the Bishop,"

There are certain heretics. . .called Waldenses, after their heresiarch, who was named Waldus, who--led by his emotions, not sent by God--founded a new sect and presumed to preach without the authority of the Bishop, without divine inspiration, without knowledge, and without literacy. He was an irrational philosopher, a prophet without a vision, an apostle without a mission, a teacher without an instructor, and his foolish disciples have led the simple folk astray in many parts of the world. 21

The Historico-theological Milieu

Waldo was neither the first nor the only divergent voice raised inside and outside of the Roman Catholic Church at this time and place. Europe was aflame with new religious movements reacting to such things as the struggle of the Papacy for supremacy, the corrupt practices of local clergy, and the currents of thought that were flowing into the area as a result of the Crusades.22 The Albigensians or the Cathari were the leading schizmatic group,23 but there were many other attacks as well. In 1140 the bishops of France wrote to the Pope that,

Everywhere in our cities and villages, not only in our schools but at the street corners, learned and ignorant, great and small, are discussing the gravest mysteries.24

In the history of this period we find reference to numerous heretical groups,

- In 1259 the Flagellants appeared. By a kind of mass contagion men, women, and children bewailed their sins and many of them marched through the streets, naked except for loin cloths, crying to God for mercy, and scourging themselves until the blood ran.25 "They proclaimed complete certainty of salvation to all who should persevere in flagellation for thirty-three days. Scourging was the one necessary sacrament. They were condemned in 1349."26

- The Beguines comprised a variety of lay groups which seem not to have been confined to any specific set of forms and to have displayed wide variety. Deanesly says they were, "the followers of Lambert le Begue, (the Stammerer). . . devout but unlettered lay people, who set great store on the use of vernacular scriptures. Lambert's followers were called from his surname, in Dutch, Beghards, (whence the English word "beggar") in Latin Beguini or Beguinae." She claims that the early Waldensians joined forces with groups of Beguinae.27

- Tanchelm began to preach in the diocese of Utrecht and early in the twelfth century his views had fairly wide currency in the Low Countries and the Rhine Valley. He attacked the entire structure of the Catholic Church, denied the authority of the Church and of the Pope, and held that at least some of the sacraments were valueless.

- Early in the twelfth century, Peter of Bruys, himself following a strictly ascetic way of life, rejected the baptism of infants, the Eucharist, church buildings, ecclesiastical ceremonies, prayers for the dead, and the veneration of the cross. The Petrobrusians re-baptized those who joined them, profaned churches, burned crosses, and overthrew altars.

- Sometimes classed with Peter of Bruys, but perhaps mistakenly, was Henry of Lausanne. Like the former he preached in what is now France and in the first half of the twelfth century. Before his death in 1145 he is said to have attracted a wide following, called Henricians. He taught that the sacraments were valid only when administered by priests who led a life of asceticism and poverty. He condemned the clergy of the day for their love of wealth and power.28

- The Adamists conducted their worship in the nude.29

- Arnold of Brescia. . .was earnestly eager to see the Church conform fully to the Christian ideal. Believing that this could not be so long as its leaders compromised with the world, he attacked the bishops for their cupidity, dishonest gains, and frequent irregularity of life and urged that the clergy renounce all property and political and physical power. . .in 1155 he was hanged, his body was burned, and his ashes were thrown into the Tiber. . . .30

- In Northern Italy, ". . .the "Pataria" had some years earlier grown up spontaneously in reaction to an increasing corrupt and politically oriented clergy." They were apparently the descendants of the Bogomils, who in turn grew out of the dualistic "Paulicians".31

In addition to these were numerous lesser movements, of which Latourette admits, "We shall probably never learn even the names of all of them."32

Even this short list demonstrates that there were questions being asked at this time, many of which are strikingly similar to those issues raised by the Poor of Lyons:

- the question of poverty and asceticism as a means of growth and/or salvation,

- questions about the role of ritual,

- activism of various sorts among the laity,

- questions about the integrity of the clergy.

- questions about interpretation and application of the Bible.33

It is likely that Waldo and his followers were influenced by some of these movements, although it is not clear how much. It would be too coincidental to see such common themes arising apart from any influence whatever. The fact is that there was a cultural and religious milieu shaping the thinking of this movement.

For example, we can place Lyonese poor nuclei in the same area of France as the Cathari, at a time when the Catharite revolution was at its height.34 Also, both southern France and northern Italy were hot-beds of dissident zeal during the very period of the rise of the Waldensians.

On the other hand, the Neo-Platonic and dualistic aspects of so many of these groups is not as evident in the teachings of the Waldensians during the earliest period. There is undoubtedly some platonic asceticism involved in Waldo' renunciation of wealth. Many of the new groups, including the mendicant orders of monks were renouncing all wealth at this time, and traveling around as beggars and preachers.35

It is important to realize that the reason they did so was not in order to relieve poverty through a more equitable distribution of goods, but because the suffering incurred from being poor was good for the soul. The material world was viewed with suspicion, and anything that served to separate one from it would bring him/her closer to the Spiritual world, that is, closer to God.36

Significantly, shortly after the time of Waldo, Boanaventure would argue that poverty had been Christ's pattern, carried on for some time by monks such as the Egyptian anchorites, "but poverty declined after the Donation of Constantine and was not revived until the thirteenth century with the foundation of religious mendicancy by Francis and Dominic." This view of history was identical to that held by the Waldensians.37

Tourn and others argue that this ascetic ideological base was not the case with the Waldensians. Their basis for renunciation of wealth was a literalistic application of Luke 9:3-6, and Mark 10:23-27, which are not ascetic. In other words, ". . .one might say that Waldensian piety was eschatological rather than dualist or ascetic."38

This may be partially true for another reason. We find no reference to the monastic literature anywhere in the early Waldensian literature. The Cistercian order, which had been organized around 1119 believed that,

. . .the rule (of St. Benedict) was not merely a guideline or a set of positive laws which can be dispensed, but rather a species of Divine Law, which like the Commandments of the Gospel, has to be interpreted, but cannot be changed or dispensed.39

This point of view, so typical of all of the orders at this time, is absent from early Waldensian thinking. They based their movement of the authority of the scriptures.40

Another distinction between the Waldensians and the monastic idealists at this time was the outward focus of the Poor of Lyons. They were not seeking primarily inner piety, but aggressive outreach to others.

". . .Waldo's case was different [than most poverty enthusiasts]. His vow did not lead him to a monastery and to a life of contemplation and obedience. He was an ordinary citizen among the poor and was determined to remain so. . .41

"For the Poor the bond of unity lay not in the sacraments but in their apostolic mission. Christian virtue, then, was in demonstrating love, and care for the brethren.

"Everyone of them, old and young, men and women, by day and by night, do not stop their learning and teaching of others."

An inquisitor quotes, in the same vein, one of the Poor who had been brought before him: "In our home, women teach as well as men, and one who has been a student for a week teaches another." 42

Thus the Waldensians were more activistic and outreaching than sacramental or reflective.43

Perhaps if there had been more dependence on monastic ideology the later history of the Waldensians would have been very different. Not long after the time of Waldo, another new order arose not far from the region of Lombardy under the leadership of Francis of Assisi. The similarities between these groups is quite striking.

Both were operating in the same area at about the same time. Francis was also untrained in theology. His followers, like the Waldensians, were unlearned. They lived in voluntary poverty, dressing in course cloth and sandals--exactly like the Waldensians. They traveled around sometimes and preached, as the Waldensians did, although the emphasis with the Franciscans was more on service while that of the Waldensians was more on preaching. Both were critical of the Roman Church's failure to fully live up to the ideals of Scripture. Both went to Rome to obtain papal approval for their orders. And this is where the similarity stops.

Francis did obtain approval from the Pope, while Waldo did not.44 Thus the Franciscans were taken into the embrace of the Church. This exempted them from persecution for the time being, and in fact, Franciscans were often leaders of the persecution of the Waldensians.

The question of the relationship of the Waldensians to the other doctrinal currents of that time is hard to determine exactly. There is no evidence of any influence from other groups on Waldo himself, until after his condemnation. Earlier, for instance, he directly denounced the Albigensians' doctrine.45

The most important point in this is that there was no ideological or theological breakthrough that occasioned the Waldensian movement.46 Their existence was not the result of any change in theology, but rather a change in theopraxy--the Poor of Lyons translated the Bible, and preached it in their own words.47 Thus, the Waldensians are an early test case in the area of lay ministry. Their main sin was to take too literally the Biblical command to, ". . .teach them to observe all that I commanded you."

Not only did they refuse to deny the right of the laity to preach and teach, they also allowed and encouraged women to teach. This had tremendous shock effect on their culture, at the same time that it probably tapped an hitherto unknown source of power.48 It would be easy to underestimate the impact that this feature had on the Europe of 1170.

It was after their excommunication that the Poor of Lyons' doctrine became objectionable to the Roman Catholic Church. More than a hundred years later, it was said,

Among all the sects, there is none more pernicious to the Church than that of the leonists, and for three reasons:

In the first place, because it is one of the most ancient; for some say that it dates back to the time of Sylvester; others to the time of the Apostles.

In the second place, because it is the most widespread. There is hardly a country where it does not exist.

In the third place, because, if other sects strike with horror those who listen to them, the Leonists, on the contrary, possess a great outward appearance of piety. As a matter of fact they lead irreproachable lives before men, and as regards their faith and the articles of their creed, they are orthodox.

Their one conspicuous fault is, that they blaspheme against the Church and the clergy, points on which laymen in general are known to be too easily led away.49

Doctrine Before the Reformation

Either in 1184 or in 1215 the Waldensians were excommunicated from the Roman Catholic Church.50 We know that in 1184 the French bishops who were called to the Council of Verona included them in the list of "condemned movements." Further, in 1190 the Bishop of Narbonne pronounced a condemnation for heresy.51

As in the case of Luther, over 350 years later, the excommunication of Waldo proved to be the occasion of increased theological polarization. Tourn argues that during this period, Waldo was influenced by "the Cathari, Pierre de Bruys, the monk Henri and others."52 From these schismatics, they heard stiff criticism of the Roman Catholic Church.

For the first time, the movement began to include radical protest in its views. Clearly, there was a need to re-define their views on the sacraments, and other features of ecclesiology, since they no longer had access to these "means of grace" through the Church. Yet the shift seems to have been minimal, especially in the area of soteriology. There was still no breakthrough in the area of salvation by grace. On the other hand, all of the changes that did occur during this period were in the same direction as later reform movements.

Adding momentum to change was the merger with some northern Italian splinter groups. These groups heard in the preaching of the Poor of Lyons views that they already held. Latourette says that the Waldensians were ". . .joined by many of the Humiliati, who had arisen in and near Milan and in that same year (1184) had come under Papal prohibition. . . They criticized prayers in Latin on the ground that they were not understood by the people, and derided church music and the canonical hours."53

These dissidents were established before the time of Waldo, and tended to have a more communal ideal in their piety. They probably had the effect of stabilizing a movement which was devoted to vagrancy by providing centers of agitation (this also made them easy to locate, and therefore vulnerable). Milan had such a welcoming attitude that they permitted the Waldensians to build their own house of prayer. This may have been the only occasion on which they could openly have such a building for the next 300 years.

The Lombards, as the North Italian group was called, had many ideas of their own. They were actually thrown out of the Waldensian movement in 1205 by Waldo, but later re-joined.

Melia, who argues that the Waldensians were not Protestant in their doctrine, can be counted on to refuse all exaggeration in the area of the Poor's evangelical beliefs. He does admit (and documents each from more than one authentic Waldensian source) the following listing of their divergent views during the period before the Hussite revolution.

- The Church of God has failed.

- The Holy Scriptures alone are sufficient to guide men to Salvation.

- The blessings and consecrations practiced in the Church do not confer any particular sanctity upon the things or persons blessed or consecrated.

- Catholic priests. . .have no authority; and the Pope of Rome is the chief of all heresiarchs.

- Everyone has the right to preach publicly the word of God

- Every oath is a mortal sin.54

- Purgatory is a dream, an invention of the sixth century.

- The indulgences of the Church are an invention of covetous Priests.

- There is no obligation to fast, nor to keep any holy day, Sunday excepted.

- The invocation of Saints cannot be admitted.

- Every honor given in the Church to the holy images of paintings, and to the relics of Saints is to be abolished.

To this list, he adds doctrines that belong to the period between the Hussite revolt and the Lutheran Revolution:

- Auricular Confession is useless, and. . .it is enough to confess our sins to God.

- The definition of the church is, "the whole of the elect from the beginning of the world to its end." and that regarding ministries, "the holy Catholic Church is the congregation of all ministers and people obeying the Divine will, and by obedience united. . ."

- It is necessary to receive the Eucharist under two kinds.55

To these I would add,

- The church and the state should remain as separate authorities.56

- The Eucharist is to be viewed as a memorial, not as a sacrifice.57

It will be seen that every one of these doctrines are the natural outgrowth of exclusion from the Roman Church. It was natural that the Poor of Lyons, feeling that they had acted out of devotion to God from the beginning, would wonder whether denial of access to the priestly functions of the Roman Church could alter their destiny. Especially with the Bible in their own language, it was natural that they would re-examine these issues, and ultimately deny Roman Catholic teaching in these areas. Therefore the rejection of priestly function in the church was probably done in reaction to the action of the Roman Church, rather than being a native sentiment of the movement.

Regarding the last point, on the Eucharist, it may be asked how the Waldensians thought they would obtain salvation, since Roman Catholic doctrine has the grace of God becoming effective through the sacraments. Here, it seems that no clear answer is available. Apparently, the worshiper is to do his/her best to be good, and ask forgiveness from God for the rest. There was also confession to a "barba" ("uncle" or teacher-leader) and prayer on behalf of the penitent.58 Unfortunately, the grace aspect of Huss' teaching seems to have been substantially lost on the Waldensians.

Given these tenets, there does not seem to be warrant for referring to "two reformations" as does Amedo Molnar--the first being the Hussite and the Waldensian movements, and the second, being the movements of the sixteenth century.59 At the same time, it must be admitted that these two movements did make a substantial though incomplete movement back toward the biblical model. The Waldensian movement was a revolution based on radical ecclesiology, but without substantial change in soteriology. Their contribution should not be disregarded any more than the Lutheran and Calvinists, who continued to accept unbiblical doctrine in the area of eschatology and ecclesiology.

Growth and Reaction

During the thirty or so years between the excommunication of Waldo and the first major genocidal crusade against them, the movement spread at an astonishing rate. There were cells of activity right across southern Europe by the year 1208 when the crusade against the Albigensians was proclaimed by Innocent III.

In this year there began a crusade against the Cathari60 akin to the one that had been going on against the Muslims for some time. This was the first time the crusade concept had been used against dissidents who called themselves Christian. "For twenty long years Languedoc and Provence in France were subjected to a blood bath which not only wiped out the most advanced culture of the time but introduced it into the Church, and from there throughout the West, the rule that any ideological deviation must be crushed by force."61

It is important to remember that this period (1150-1300) were the years of the zenith of papal temporal power. Innocent III described himself as "set between God and man, lower than God but higher than man, who judges all and is judged by no one. . ."62 He declared that, "the priesthood was as superior to the kingship as the soul to the body," and he informed the nobles of Tuscany that, "just as the moon derives its light from the sun . . .so too the royal power derives the splendor of its dignity from the pontifical authority."63 As has been the case so often in history, greater political power for the institutional church has been bad news for Christian minorities.

This was also the pattern that would characterize Roman Catholic reaction to the Waldensians for the next 450 years. The history of the Waldensians during this period is an incredible litany of genocidal disaster. This was the period of the inquisition in Europe, and it is through the well kept records of the inquisition that we follow the spread of the Waldensians movement throughout Europe. Tourn lists some of the major persecutions after the crusade of 1208:

- We know that at the beginning of the 14th century there were enough Poor remaining in France that the inquisitor Jacques Fournier, who later became Pope Benedict XII, undertook court trials against them.

- The transference of the papacy to Avignon in the middle of the 14th century was apparently the signal for a brutal repression against Waldensians in the Dauphine, for the beleaguered Pope was evidently not disposed to tolerate any expression of dissidence so near to his exiled see.

- In the year 1380. . . [a severe] round-up was begun under the inquisitors Martin of Prague and Peter Zwicker. These two were commissioned to bring to trial or to force the conversion of Waldensians through much of Europe.

Their systematic effort began in Bavaria, continuing in the following year in the region of Erfurt, and in 1392 in the province of Brandenberg. The inquisitors then proceeded to Stettin, where they held a trial of 400 Waldensians.

Their reports speak of activities in various cities of what are now Germany, Czechoslovakia and Hungary, and of their success in the city of Bern, Switzerland, in getting 130 suspects to abjure heresy and return to the Church's fold. They reported a similar success in Fribourg with some 50 Waldensians. - . . .in the latter part of the century the inquisition was resumed in full intensity under the direction of a Franciscan, Francesco Borelli. So obsessed was this monk with his pursuit of heretics that it was said that every prison from Embrun to Avignon was full to overflowing. As a result, Pope Gregory IX himself had to appeal for alms for the hapless prisoners.

- . . . in 1450, the inquisitors were sent in to deal with Alpine dissidents. In that year the whole valley of Luserna was placed under interdiction on the charge of having resisted the authorities.

- Another inquisitorial sweep took place in 1475, including interminable court trials against anyone who failed to cooperate fully in the drive. . . .the counts of Luserna themselves were. . . charged with being too lenient toward the Waldensians--for which they were duly warned and subjected to heavy fines.

- . . .Charles I at last called for full scale military action against the dissidents, and was joined, from the French side, by the declaration of a crusade against the Waldensians which lasted from 1487-89. The latter was directed by the infamous papal legate, Alberta Cattaneo

. . . There the governor of Savoy, with the full consent of Charles VIII of France, undertook a veritable and thorough going crusade against the hapless population. As in other places and times in the Middle Ages, it was under the patronage of the Pope and organized by his legate

. . .[the village of] Pragelato found itself squarely in the path of the crusaders, so that it was invaded and sacked in the winter of 1487. A fate similar to that of Pragelato was in store for the Waldensians in the valleys of Argentieres and Vallouise. These folk had been consistently pacifist by tradition, so that they did not resist when the invaders came. The crusaders then proceeded to level their villages, destroying every trace of the Waldensians heritage. - Francis I. . .in 1545 named the president of Aix's parliament personally to lead a papal army from Avignon to clear the area entirely of Waldensian presence. The Luberon folk were suddenly caught in a vise.

. . .The mercenary soldiers engaged for the sweep did not stop until they had devastated the whole region and obliterated every trace of the Waldensian villages. A few survivors did manage to escape to Switzerland, but the lot of all the rest was either death by the sword or life sentences as galley-slaves on French ships. - . . .On June 5, 1561, the town of San Sisto, with its 6,000 inhabitants, was burned to the ground.

. . .Guardia Piemontese, its neighbor, was likewise destroyed. Prisoners were burned like torches, sold as slaves to the Moors or condemned to die of starvation in the dungeons of Cosenza. The massacre reached its height at Montalto Uffugo on June 11th. On the steps in front of the parish church, 88 Waldensians were slaughtered one by one, like animals brought to market. - If the military operation lasted only a few weeks, the work of Catholic indoctrination, Jesuit style, continued for years. The Jesuits were determined to obliterate every evidence that Waldensians had been present in Calabria. They almost succeeded, except in one small respect: there is still a hint of the Provencal language in the daily speech of the inhabitants.64

The list of atrocities goes on and on, in fact far too long for detailed consideration here.65 The point that becomes clear is that every effort was made on numerous occasions to eliminate the Poor of Lyons in the customary way. At various points this policy was close to final success. Yet, the Waldensian movement was never eliminated.

Another tactic that was employed briefly with success by Pope Innocent III was to take advantage of the differences between Waldo and the Lombards in 1208 to win the Poor Men back to the Church. Beginning in 1208 he encouraged the formation and spread of Pauperes Catholici ("Poor Catholics") who under ecclesiastical direction would follow such of the practices of the Waldenses as the Church could approve. By this means many who had been attracted by the Poor Men were held or won back.66

Nevertheless, the Waldensians continued to grow at a surprising rate. The pattern of growth appears to have been the result of systematic underground discipleship and witnessing.

. . .men and women, great and lesser, day and night do not cease to learn and teach; the workman who labors all day teaches or learns at night . . .When someone has been a student seven days, he seeks someone else to teach, as one curtain pulls another. Whoever excuses himself, saying that he is not able to learn, they say to him, "Learn but one word each day, and after a year you will know three hundred, and you will progress."67

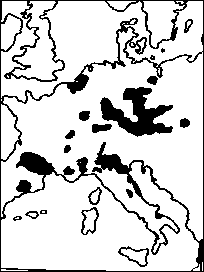

Tourn has a remarkable map showing areas where Waldensians presence can be documented, reproduced here.68

Map of Europe shows shaded patches all over western and some of eastern Europe

In 1517 - the very year of Luther's protest--the Archbishop of Turin made record of a pastoral visit to the Alpine valleys in which he singled out for concern the ongoing presence of Waldensian groups practicing their faith.69

Involvement with the Hussites

When Jon Huss revolted against the authority of the Roman Catholic Church, it was not another peasant revolt but a well reasoned attack aimed at the roots of papal authority and doctrine. Huss was a scholar lecturing at the University of Prague. He taught that the Bible was the sole authority for faith and practice, and salvation by faith. He was promised safe conduct to the Council of Constance to answer for his views, but was seized and burned at the stake anyway. At this point the population of sections of modern Austria and Chechoslovakia rose in open revolt.

One new twist in this revolt was that some fought when attacked by the inevitable papal army. In the same way that the Paulicians had earlier, they actually fought the Roman Catholic Church to a standstill in the 1400's. The fortress that they later formed at Tabor gave one group of them the name Taborites.

When word of this revolution reached the Waldensians, they reacted with excitement. They promptly dispatched several "barbas" ("uncles", the term used by Waldensians for their teachers)70 to go to Bohemia and learn what was happening. There followed a series of meetings between leaders of the two groups which led to great benefit for the Waldensians. They received from the Hussite movement training in theology which was to prove very helpful to future generations.

As a result, the barbas during this period were capable of reading theological works in Latin, of studying mathematics, and knowing enough botany and rudimentary medicine to permit them to deal with simple diseases. Their activity in ministerial tasks likewise became more organized, rigorous and systematic than before. A young Waldensian whose gifts and resolve marked him for service in the community would be apprenticed to an experienced barba for a period of several years. After becoming familiar with the various places to visit, learning languages and studying the Bible more deeply, the young barba would then visit the different clandestine scholae or underground schools.71

It is also interesting to note that although the Waldensians had almost always been pacifist, on one occasion they raised money for the Bohemian war chest. On another occasion, at Prali, a pitched battle between the local populace and the crusaders ended by Count Hugo pulling back his troops.72

The Reformation

Tourn states that,

Relentless inquisition, crusade and pillage had done their efficient work, so that by the end of the 15th century a veil of silence hung over much of the Waldensian world.73

Yet the Waldensians still existed. By now, they were almost exclusively concentrated in the Alpine valleys that had served as their main stronghold all along.

When the reformation erupted in 1517, the Waldensians were eager to join forces with the new fellow-revolutionists. We know that as early as the year 1526, a general assembly of Waldensians held at Laus, in the Chisone valley, was so eager to make personal contact with the new movement that it made the decision to send a deputation across the Alps.74

Luther, who so strongly denounced the Hussites at first, discovered during the Liepzig Disputation that he agreed with Huss. Later he said "We were all Hussites without knowing it!"75 Eventually, he wrote a preface to the Taborite Confession of Faith, in which he referred to the Hussites as "Waldensians".

No official ties were forged between the Waldensians and the other Protestant Churches until 1532. In that year, the Synod of Chanforan was held, in which the Waldensians became a part of the reformed Church based in Geneva. For the Reformed, Farel led the negotiations, which were troubled, because of the Waldensian insistence on the separation of church and state, as well as other doctrinal differences.76 The Swiss reformers also called on the Waldensians to put an end to confessions, fasts and "meritorious Sundays," and to introduce an emphasis on the doctrine of predestination.77

In the same year, the Geneva Reformers helped the Waldensians do a new translation of the Bible. The task was entrusted to Olivetan, a relative of Calvin's, who retired secretly to a village in the Alps to do his work.

The remarkable translation he produced (for which Calvin himself wrote the Preface) has come to be known as the "Olivetan Bible," the first of the French Reformation. Printed in Neuchatel, it was delivered to the Waldensians in 1535.78

Many of their worst trials, including massacres, were still ahead of them in 1532, but they were now a part of an international movement. Because they were no longer alone as an isolated sect, and because their doctrine was essentially reformed, they pass beyond the scope of this study.

Conclusions

It is questionable whether the Waldensians ever exceeded 100,000 functional members at any one time before the Reformation. Yet when one considers that they existed in some force for almost 350 years before the reformation began, it is evident that many generations, and therefore many times their total were affected.

No one knows, even roughly, the total number killed in the persecutions the Waldensians endured, but the lowest estimates must run into the several tens of thousands. It is unlikely that any group other than the Anabaptists and Jews can point to a comparable history of prolonged universal persecution. Their amazing survival makes them different, than the other schizmatic groups that began at the same time as well. The crime which precipitated such suffering was their desire to exercise their birthright in the Body of Christ according to the New Testament--the practice of their own gifts and ministries

The Waldensian Church still exists today in several locations.79 Unfortunately, the fusion with the Reformed Church has not resulted in the rapid ferment of outreach that once characterized the movement. Nevertheless, the fact that they remain in existence at all is a strong testimony, and perhaps a galling reminder to some, that the effort to disenfranchise the laity from their right to minister will be frustrated by the power of the Holy Spirit Himself.

Footnotes

1. Giorgio Tourn, The Waldensians: The First 800 Years (1174-1974) Translated from the Italian by Camillo P. Merlino, Charles W. Arbuthnot, Editor (Torino, Italy: Claudiana Editrice, 1980) p. 5

2. See the relevant portions of the Donation of Constantine in translation Brian Teirney, The Crisis of Church and State: 1050-1300, (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, Inc. 1964) p. 21.

3. The importance attached to this link can be seen in the comment of a later Presbyterian historian, C.H. Strong, ". . . if it be true that this once fearfully persecuted people is the true connecting link between the Apostolic Church and the Protestant Reformation, then our interest in their history must be greatly heightened. With this view of their antiquity there could scarcely be an incident concerning them that would not be magnified into something of importance." C.H. Strong, A Brief Sketch of the Waldenses, p. 23,24.

4. Perrin. -- Histoire des Vaudois et des Albigeois &c., a Geneve, pour Matthieu Berjon, CIC.ICI.XVIII (1618). Two Vols., usually bound in one; Dated from Lyons, in Dauphiny, 1 January, 1618. Cited in Alexis Muston, D.D., The History of the Waldenses Vol. II, p. 398.

5. "In the `Acts of the Synods of Dauphiny' (Synod held at Grenoble in 1602) we read, that the pastors of the Embrunois and of the Val Cluson (which was then included in Dauphiny) were requested to collect "all sorts of documents bearing on the history of the life, doctrine, and persecutions of the Albigeois and the Vaudois." Alexis Muston, D.D., The History of the Waldenses Vol. II, p. 398.

6. The Waldenses, (Presbyterian Board of Publication and Sabbath-School Work, 1912) p. 31 The MSS were given to Sir Samuel Moreland, who also wrote history on them. Both of these authors are roundly refuted by Pius Melia, D.D., The Origin, Persecutions, and Doctrines of the Waldenses, (London: James Toovery, 1870).

7. See below, "Doctrine Before the Reformation."

8. Muston says of Perrin, "Not only did Perrin fail to make proper use of his rich materials, but he has even been accused of having employed them unfaithfully," and of Leger, "Leger is the most diffuse, and one of the most superficial of all our historians. He owes his importance partly to the epoch in which he wrote, and to the imposing form of his work. He is often incorrect, credulous, and carried away by his feeling; but the latter fault was almost inevitable in a contemporary author, himself the victim of the events which he records. Alexis Muston, D.D., The History of the Waldenses Vol. II, 399,402.

9. C.H. Strong, A Brief Sketch of the Waldenses, and The Waldenses, (Presbyterian Board of Publication and Sabbath-School Work, 1912) p. 29 explains the lack of documentation at several points saying, "The Waldenses complain, that it has been the cruel policy of their persecutors to destroy all the historical memorials of their antiquity."

10. Pius Melia, D.D., The Origin, Persecutions, and Doctrines of the Waldenses, pp.59-85. "That the principal reason for which the Waldenses were punished in Piedmont was not precisely their religious belief, but their having been rebellious against the orders of the Sovereign and the laws of the country in which they lived. . ." He goes on to point out that they had killed an officer of the inquisition in the neighborhood, without speculation as to why they would want to attack a friendly inquisitor (p. 83).

11. Giorgio Tourn, The Waldensians is a good history, written from a friendly but fair point of view. This source takes cognizance of all of the critical findings that I have been able to locate. Tourn seems to be very judicious in his use of the sources, rejecting Waldensian legends, even though he is a Waldensian pastor. He should however, be criticized for down-playing the influence of dualistic asceticism on Waldensian doctrine, and perhaps for the use of one source that did not appear in other literature.

12. The Chronicler was Richard, Monk of Cluny, "Rerum Italicarum Scriptores", tom.iii, p. 447 et seq. Reprinted in Pius Melia, D.D.,The Origin Persecutions and Doctrines of the Waldenses, with translation, pp.1-3. For a clearer but abridged translation, see Giorgio Tourn, The Waldensians, p. 3,4.

13. Bernard Gui, Manuel de l'Inquisiteur, Partially reprinted in Giorgio Tourn, The Waldensians, p. 3,4. For a more complete text of the source in translation, see Jeffrey Burton Russell, Religious Dissent in the Middle Ages, (New York: John Wiley & Sons, J1971) pp.42-52. including methods to use in an inquisitorial session with a Waldensian,

14. Bernard Gui in Jeffrey Burton Russell, Religious Dissent in the Middle Ages, p. 44.

15. This translation was done by priests in Lyons, Bernard Ydros, and Steven de Ansa who were paid for their work by Waldo. F. Steven de Bellavilla, "Scriptores Ordinum Praedicatorum," reproduced with translation in Pius Melia, D.D., The Origin, Persecutions, and Doctrines of the Waldenses, pp. 9-14. This source says he had met several times the later translator. Writing in the early 1200's, he would be considered a good source. He describes the excommunication of The Waldensians, and their practice of changing disguises frequently (from cobbler to merchant etc.) as they traveled around, to avoid detection.

16. This short description by Mapes "De Nugis Curialium," one of the earliest reference to The Waldensians, is among the manuscripts of the Bodleian Library (851) at Oxford. Mapes goes on to relate that they were forbidden to teach, and concludes, "Naked, they follow a naked Christ. Their beginnings are humble in the extreme, for they have not yet much of a following, but if we should leave them to their devices they will end by turning all of us out." Partially reproduced in Giorgio Tourn, The Waldensians p. 14.

17. This is an example of what was called "ignorance" and "illiteracy" by Mapes.

18. "Direct personal experience of God and its propagation through preaching, unless adapted to the sacramental life of the church, constituted [a] . . .greater threat: for, carried to its conclusion, it meant nothing less than entirely renouncing the arbitrament of the church and denying its raison d'etra as the expression of God's saving will on earth." Jeffrey B. Russell ed., Religious Dissent in the Middle Ages, p. 105.

19. Pius Melia, D.D., The Origin, Persecutions, and Doctrines of the Waldenses, p. 89.

20. Note the inconsistency in the claim that they were illiterate, yet they translated the Bible and other books "in common speech". While many no doubt were illiterate, it is likely that for others, their illiteracy consisted of inability to read languages other than Provencal.

For an example of the logic used to reject their right to preach, see F. Moneta, "Venerabilis Patris Monetae Cemonensis Ordinis Praedicatorum adversus Catharos et Waldenses, Libri quinque", (Rome: Thomas Augustin Ricchini, 1743) original with translation in Pius Melia, D.D. The Origin Persecutions and Doctrines of the Waldenses, pp.4-9.

21. Alan of Lille, Against The Waldensians (1200-1202), partially reprinted in translation in Jeffrey Burton Russell, Religious Dissent in the Middle Ages, pp. 52,53.

22. For instance, the Cathari were widely believed to have been influenced by Manichaen doctrine, denied by many today. However, they probably were influenced by the Paulicians and the Bogomils, who were from the Balkan region. So, Kenneth Scott Latourette, A History of Christianity Volume I: to A.D. 1500, (New York: Harper & Row Publishers, 1975) p. 454. Latourette says, "The Cathari were but one expression of the religious ferment, chiefly Christian in its forms, which profoundly moved the Latin South of Europe in these centuries." p. 453.

23. For a good succinct evaluation of the Catharite heresy, see Jeffrey B. Russell ed., Religious Dissent in the Middle Ages, (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1971), pp. 55-76.

24. Quoted in Emilio Comba, D.D., History of the Waldenses of Italy, (London: Truslove & Shirley, 1889), p. 16 He adds, "It seemed indeed as if the foundations of the Church were being upheaved; storms of ideas and lurid lights were arising on all sides. . .These were intermingled with new interpretations of the Gospel which were audaciously progressive, and with opinions, which on the contrary, sought refuge in primitive Christian tradition against the innovations of Rome." Comba, although he is a Waldensian pastor, rejects the antiquity of The Waldensians.

25. Kenneth Scott Latourette, A History of Christianity Volume I: to A.D. 1500, p. 448.

26. Margaret Deansly, A History of the Medieval Church 590-1500 (London: Methuen & Co. Ltd., 1972) p. 219.

27. Margaret Deansly, A History of the Medieval Church 590-1500 (London: Methuen & Co. Ltd., 1972) p. 221.

28. Kenneth Scott Latourette, A History of Christianity Volume I: to A.D. 1500, p. 449,450.

29. Margaret Deansly, A History of the Medieval Church 590-1500 (London: Methuen & Co. Ltd., 1972) p. 219.

30. Kenneth Scott Latourette, A History of Christianity Volume I, p. 450-451.

31. Giorgio Tourn, The Waldensians, p. 15.

32. Kenneth Scott Latourette, A History of Christianity Volume I: to A.D. 1500, p. 449.

33. For the state of biblical scholarship in the 14th century, see William J. Courtenay, "The Bible in the Fourteenth Century: Some Observations" in Church History, Vol. 54 No. 2 (Sp. 1985) pp. 176-187.

34. The same general area also gave rise to the Cistercians in the 1100's and the Franciscans and Dominicans in the 1200's-- three of the main orders of this period. Kenneth Scott Latourette, A History of Christianity Volume I: to A.D. 1500, p. 453.

35. Biller identifies distinct orders of "brothers" and "sisters" in the later fifteenth century Waldensians who like the Barba, traveled and preached for at least part of their careers (there may have been a later contemplative phase for the older brothers). Biller shows that the rite of entry to the brotherhood included the "profession of the three monastic vows. . .greater strictness [than other mendicant orders] . . .a requirement of virginity, not just celibacy in a candidate, automatic expulsion for a sexual lapse, a longer period of probation after profession of vows, twelve years in one case. . ." Peter Biller, "Multum Ieiunantes et se Castigantes: Medieval Waldensian Asceticism" in Monks, Hermits and the Ascetic Tradition: Papers read at the 1984 Summer Meeting and the 1985 Winter Meeting of the Ecclesiastical History Society, (London: Basil Blackwell, 1985) pp. 218,219.

36. See a concise analysis of Asceticism based on the writings of Augustine in Henry Chadwick, "The Ascetic Ideal in the History of the Church," in Monks Hermits and the Ascetic Tradition, pp. 1-23. This period was formative for the history of asceticism in the church, because the overwhelming influx of so-called "converts" after Constantine was threatening to erase the distinction between Christian and pagan. In the face of social pressure to become Christian, millions were joining the church without having been converted. Thus, in addition to the dualistic reasons for asceticism (suspicion of the material world) there was the effort to put distance between one's self and the nominal Christians (see pp. 8-9).

37. James Doyne Dawson, "Richard Fitzralph and the Fourteenth-Century Poverty Controversy", Journal of Ecclesiastical History, Vol. 34, #3 (Jul. 1983) p. 317.

38. Eschatological, because concerned with making it to heaven (see note 38 below). However, the other ascetic orders also were concerned with making it to heaven. Giorgio Tourn, The Waldensians, p. 50.

39. W. E. Goodrich, "The Cistercian Founders and the Rule: Some Reconsiderations," in Journal of Ecclesiastical History, Vol. 35, No.3 p. 358 (July 1984).

40. Although Pius Melia claims that, "It is therefore beyond doubt that, before the time of Luther and Calvin, the Waldenses admitted all the books of the [Catholic] Bible. . ." (e.g. including the Apocrypha) the only evidence he gives is the presence of two portions of apocryphal books in translation in the Cambridge collection of Waldensians mss. Pius Melia, D. D., The Origin, Persecutions, and Doctrines of the Waldenses, p. 93,98. However, this conclusion seems unwarranted. The Waldensians definitely rejected the existence of purgatory during the early period, and claimed that it was foreign to the scriptures. They also argued that there was nothing anyone could do once a person died, as can be seen from the following early record of the Inquisition.

". . .one who does good will go to paradise, and one who does evil will go to hell and damnation; purgatory does not exist. Indeed, whoever believes in purgatory is condemned already. Further, charities after one's death should not be done, for charities after death have no value; that they do not profit the one who does them if they are not done before death. . ." "Interrogation of Filippo Regis" at his trial in 1451, published by G. Weitzecker, Processo di un valdese nell'anno 1451, in Rivista Cristiana IX (1881) pp. 363-67, Partially reproduced in translation in Giorgio Tourn, The Waldensians, pp. 55,56.

These views would be impossible to argue if the book of II Maccabees was viewed as canonical. There is no statement in any Waldensian writing affirming the canonicity of the Apocrypha. These books, like the writings of the fathers (which are also found in Waldensian translation) were apparently used as supplemental material, as indeed they were so viewed by most of the Roman Catholic Church during this period.

41. The established orders of monasteries were obtaining great wealth during this period. See Bainton's insight that when reaching new areas during a time when currency was worthless, only a self-supporting monastery was in a position to survive. Later, as land was donated, the serfs were donated along with it. The monks would accept the serfs, and so became land major lords. "Altogether they were the most enterprising businessmen of their day." Roland Bainton, "The Ministry in the Middle Ages," in The Ministry In Historical Perspective, H. Richard Niebuhr and Daniel D. Willians, Editors, (New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1956) pp. 86,87.

42. Giorgio Tourn, The Waldensians, p. 6,21,39.

43. By the end of the 15th century Biller is able to describe the Waldensian "brothers" as giving, ". . .a two dimensional picture of the asceticism of a strict and clandestine mendicant Order." Yet one has to remember that this was almost 300 years after the movement had begun. One only has to compare the church in 350 AD to the church in Acts to realize how much things may have changed in such a long period. Peter Biller, "Multum Ieiunantes et se Castigantes: Medieval Waldensian Asceticism" in Monks, Hermits and the Ascetic Tradition, p. 223. When taking confession, "their penance was heavier than that imposed by the priests in the Church." For instance, they demanded "fasting one or two days a week for a year or several years" for excessive love-making with one's wife or husband (p. 226).

44. The reason for the rejection of Waldo is given as his ignorance. Yet, Francis was not rejected. Of course, there were different popes involved, and the church had the experience of The Waldensians to reflect on at the time of Francis. I think that the only visible difference of importance was the fact that Waldo had the Bible translated. Therefore, when the Poor of Lyons preached, it was with a Bible in their hands in the vernacular. This was probably a level of authority too threatening to tolerate.

45. Edward Peters ed., Heresy and Authority in Medieval Europe: Documents in Translation, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1980) p. 140.

46. In the year 1180, Henri de Marcy, the Pontifical Delegate, was in southern France to organize a campaign against the Cathari, and there encountered Waldo. He called on Waldo to sign a statement of adherence to the Roman Catholic faith, and without hesitation he did so. Giorgio Tourn, The Waldensians, p. 11.

47. ". . .the praxis of the primitive church plays a normative role for The Waldensians. . . it constantly occurs in their theological declarations, next to the reference to the dominant authority of Scripture. . ." Milic Lochman, "Not Just One Reformation: The Waldensian and Hussite Heritage." Reformed World. Vol. 33, No. 5 (Mar. 75) p. 219.

48. Bernard Abbot Fontis Calidi, Adversus Valdensium Sectam, (Biblioteca Veterum Patrum, Vol. xxv. p. 1585, 1677) given partially with translation in Pius Melia, D.D., The Origin, Persecutions, and Doctrines of the Waldenses, pp. 14-16.

49. Gretser, Contra Valdensius IV, Given in translation in Emilio Comba, D.D., History of the Waldenses of Italy, p. 3, 4.

50. Melia says, "The Waldenses were condemned, in fact, by Pope Lucius III., at a Council held in Verona, in the presence of many Bishops and of the Emperor Frederick, in the year 1184, with these words: `By Apostolical Authority, and by means of this Constitution, we do condemn every heresy, whatever name it bears, and principally the Catharites and the Patherines, and those who, with a wrong name, call themselves, with Deception, the Humbled or the Poor of Lyons.'" Pius Melia, D.D., The Origin, Persecutions, and Doctrines of the Waldenses, p. 16. Likewise, Margaret Deansly, A History of the Medieval Church 590-1500 (London: Methuen & Co. Ltd., 1972) p. 221. But Tourn says that this was only a prohibition of their preaching. He says that they were not definitively condemned for heresy until the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215. Giorgio Tourn, The Waldensians, p. 232.

51. The reason given was "obstinacy." Giorgio Tourn, The Waldensians, p. 12.

52. Giorgio Tourn, The Waldensians, p. 12. See also Deansly, ""Margaret Deansly, A History of the Medieval Church 590-1500 (London: Methuen & Co. Ltd., 1972) p. 221

53. Kenneth Scott Latourette, A History of Christianity Volume I: to A.D. 1500, p. 452. Tourn adds that The Waldensians struck a chord with the tone of northern Italian piety. The Pateria were very receptive to The Waldensians in this region. They also met some of the followers of Arnold of Brescia, the disciple of Abelard, who had travelled all over Europe making the acquaintance of various dissident groups and had even started a popular movement in Rome. It was Arnold who first advanced the notion of a complete separation between religious and political powers." Giorgio Tourn, The Waldensians, pp. 15,16. It is in the addition of the North Italian dissidents that The Waldensians could claim some pre-existence. There had been resistance to Papal claims in this area for some time, but it was not based on evangelical doctrine, as some protestant writers assert.

54. This tenant led to added persecution in a day when fealty oaths were the basis of society. The Waldensians were outside the law, because they refused to swear allegiance to anyone. Some Inquisitors claimed that they were allowed to swear a limited number of oaths under torture in order to save themselves and others. Bernard Gui, "Manuel de l'Inquisiteur", in Jeffrey Burton Russell, Religious Dissent in the Middle Ages, pp. 51,52.

55. Pius Melia, D.D., The Origin, Persecutions, and Doctrines of the Waldenses, pp. 101-129. This section of Melia's book not only cites several original Waldensian and inquisitorial documents for each point in the original and in translation, but in addition, each doctrine mentioned is answered from the Roman Catholic point of view. Melia cites the scriptural and "de fide" documents with references that set forth the Roman Catholic position on each point. Such a defense is unusual and hard to find, especially in such condensed form.

56. According to Tourn, ". . .in Waldensian thinking one cardinal point had stood out from the beginning: an insistence on a clear separation between the civil power and the exercise of religion. . ." Giorgio Tourn, The Waldensians, p. 70. This idea seems to also underlie numerous claims by inquisitors that The Waldensians rejected the authority of all earthly princes. It is likely that they were actually rejecting the right of secular rulers to lead pogroms supposedly based on religion.

57. A typical witness to this view is Raymond de Costa's description of a Waldensian eucharist, ". . .bless, in the name of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit, this bread, this fish, [a distinctive Waldensians addition] and this wine, not as a sacrifice and offering, but as a simple commemoration of the most holy supper which Jesus Christ our Lord instituted. . .," From the "Testimony of Raymond de Costa at his trial in 1320," published by J. Duvernoy, Le Registre d'Inquisition de Jacques Fournier, Toulouse, 1965. partially reproduced in Giorgio Tourn, The Waldensians, p. 41,42.

58. Tourn says, "The fact, for instance, that any true believer could administer the sacrament of the Lord's Supper indicates that the hierarchical structure of the Church with its sacerdotal power had been overcome." Yet it is not clear what went in its place. Giorgio Tourn, The Waldensians, p. 50, 51. One of the statements in a document called, "Waldo's statement of Faith", dated by Tourn 1180 is, "We believe also that anyone in this age who keeps to a proper life, giving alms and doing other good works from his own possessions and observing the precepts from the Lord, can be saved." p. 14. This author was unable to confirm the authenticity of this source.

59. So also, Jan Milic Lochman, "Not Just One Reformation: The Waldensian and Hussite Heritage," in Reformed World, Vol. 33 No. 5 (Mar. 75) p.220.

60. The Cathari were called Albigensians because their main city was Albi in southern France.

61. Giorgio Tourn, The Waldensians, p. 18. Not everyone agreed with coercion. Genoa and Piacenza, for instance, refused to include in their legislation any laws against the heretics; Cremora advertised itself as a kind of free zone for any escapees from the crusade of 1208. (p. 26).

62. "Sermon on the consecration of a pope", in Brian Teirney, The Crisis of Church and State: 1050-1300, pp. 131,132.

63. Documented in Brian Teirney, The Crisis of Church and State: 1050-1300, p. 128.

64. Giorgio Tourn, The Waldensians, p. 36, 46 52 63, 64, 65 88-91.

65. The list is too long in some cases. Protestant authors have been accused of exaggerating the purges, and there are accounts that seem to take morbid delight in the sins of the Roman Catholic Church at the expense of truth.

66. Kenneth Scott Latourette, A History of Christianity Volume I: to A.D. 1500, p. 452.

67. "The Passau Anonymous: On the origins of Heresy and the Sect of The Waldensians," in Edward Peters, Heresy and Authority in Medieval Europe, p. 150-153.

68. Giorgio Tourn, The Waldensians, p. 61. He also warns that not all references to Waldensians are to be believed, "heretical tendencies of every sort were called `Waldensian.' One remembers that Joan of Arc was condemned for her `Waldensianism.' In the Index of the Flemish Church, Waldensian meant a mysterious character, close to the world of witches and sorcerers, worshipers of the devil and practitioners of black magic. Fascination with this view has rewarded us with verbal accounts by inquisitors and also some remarkable miniatures by Flemish artists, such as those picturing Waldensians flying on brooms or participating in the nightly excursions and dances of witches." p. 40, 41 He also produces a plate of one of the broom flying pictures on after p. 46.

69. Giorgio Tourn, The Waldensians, p. 66.

70. The practice of calling their leaders "uncles" stemmed from the desire to literally obey the command in the gospels to "call no man father. . .[or] teacher" (Mt. 23:8-10), and because the term was deceptive and helped keep secret who their leaders were.

71. Giorgio Tourn, The Waldensians, p. 59,60.

72. Giorgio Tourn, The Waldensians, p. 64,65. There were also other incidents of violence, though few in number. ". . . The Waldensians assassinated the inquisitors Peter of Verona and Conrad of Marburg; we know also that not a few priests in Bohemia who were caught up in the repression there came to the same end."(p. 48).

73. Giorgio Tourn, The Waldensians, p. 64

74. Giorgio Tourn, The Waldensians, p. 69

75. Quoted in Jan Milic Lochman, "Not Just One Reformation: The Waldensian and Hussite Heritage." Reformed World. Vol. 33, No. 5 (Mar. 75) p. 221.

76. Cameron thinks that this Synod was not an orderly meeting as Tourn suggests, but a series of discussions between various clusters of Waldensians and Reformed over a period of time, perhaps punctuated by one major meeting. Unfortunately, based on the documents he analyses, it is hard to understand his point. He admits that such a meeting did occur, and that the outcome was as claims, but he refers to it as the "The myth of Chanforan." Euan Cameron, The Reformation of the Heretics: The Waldenses of the Alps, 1480-1580, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984) pp.138-144.

77. The Waldensians agreed. Giorgio Tourn, The Waldensians, p. 70-73.

78. Giorgio Tourn, The Waldensians, p. 73.

79. See their reports from the River Platte along with some commentary on their organization and makeup in Reformed World, Vol.30,31.

Bibliography

Cameron, Euan. The Reformation of the Heretics: The Waldenses of the Alps, 1480-1580. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984.

Comba, Emilio, D.D. History of the Waldenses of Italy. London: Truslove & Shirley, 1889.

Courtenay, William J. "The Bible in the Fourteenth Century: Some Observations." Church History. Vol. 54, No. 2 (Spring 1985): 176-178.

Dawson, Doyne. "Richard Fitzralph and the Fourteenth--Century Poverty Controversy". Journal of Ecclesiastical History. Vol. 34, No. 3, (July 1983).

Deansly, Margaret. A History of the Medieval Church 590- 1500. London: Methuen & Co. Ltd., 1972.

Goodrich W. E. "The Cistercian Founders and the Rule:Some Reconsiderations,". Journal of Ecclesiastical History, Vol. 35, No.3, July 1984.

Latourette, Kenneth Scott. A History of Christianity Volume I: to A.D. 1500. New York: Harper & Row Publishers, 1975.

Lochman, Jan Milic. "Not Just One Reformation: The Waldensian and Hussite Heritage." Reformed World. Vol. 33, No. 5 (Mar. 75).

Melia, Pius D.D. The Origin, Persecutions, and Doctrines of the Waldenses. London: James Toovery, 1870.

Muston, Alexis D.D. The History of the Waldenses Vol. I& II. Rev. John Montgomery, translator. London: Blackie & Son, 1875.

Niebuhr, H. Richard, and Willians, Daniel D. ed. The Ministry In Historical Perspective. New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1956.

Reformed World, Vol. 30,31

Russell, Jeffrey Burton. Religious Dissent in the Middle Ages. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1971.

Sheils W. J. ed. Monks, Hermits and the Ascetic Tradition. London: Basil Blackwell, 1985.

Strong, C. H. A Brief Sketch of the Waldenses. London: Lawrence, Kansas: J.S. Boughton Publishing Co., 1893.

Teirney, Brian. The Crisis of Church and State: 1050-1300. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1964.

Presbyterian Board of Publication and Sabbath-School Work. The Waldenses. Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publication and Sabbath-School Work, 1912.

Tourn, Giorgio. The Waldensians: The First 800 Years (1174-1974). Translated from the Italian by Camillo P. Merlino, Charles W. Arbuthnot, editor. Torino, Italy: Claudiana Editrice, 1980.